Once he overcame the shock and awe of discovering his true parentage and true heritage, Canadian musician, author and painter Tom Wilson embraced his newly revealed connection to his First Nations culture and has used his remarkable creative talents and searingly honest approach to life to continue to process each new lesson learned, each new tradition explored.

It has been less than three years since Wilson found out that the people who he thought were his parents were not, the identity of his birth mom (who it turned out, he always thought was his cousin} and the fact that she was from the Mohawk nation, thus revealing his own First Nations ancestry. George Wilson, his perceived father for decades, was of Irish Canadian descent, while his wife, Tom’s aunt Bunny, was of French-Canadian descent.

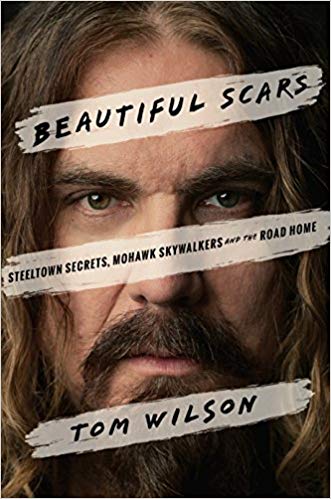

Beginning with his revelatory 2017 autobiography Beautiful Scars, and on through an onslaught of brilliant visual artworks and as well as the poetry and melodies of his music, Wilson’s continuing journey of truth and personal reconciliation with is past, is also a mirror on the current national conversation around reconciliation between Canada’s First Nations people and the subsequent generations of European settlers – and beyond.

“I realized that I can’t necessarily be in the driver’s seat of this movement, but I can be a part of it. And, really, that goes for anybody. And now it’s time for me to actually do my part. I have been involved with a restoration of a residential school just outside Brantford, Ontario in Oshweken, and I will continue to find my way in other aspects of this process. But, once again, I am learning; I am just shaking hands with a culture that I have just been introduced to, you know what I mean?” he said.

“And when it comes to this process of reconciliation and healing, we have to be gentle with one another. Jesus, we really have to take our time and be kind to one another, because that is possibly the first step in getting things done and going in the right direction. This world has got to be more gentler with one another. Moving forward, as this journey continues, I have to show honour and love and respect to my culture. I have to step in and be a voice for healing in this country. Like I said, I am not in the driver’s seat, but I am one of the passengers along the way.

“I have always believed in the power of art to bring people together. I guess that’s why I have been doing this for 47 years, really, is to be a bit of a vessel for that. That’s always been my intention and my belief to inspire people to be a little more loving. Art has no mandate; you know what I mean? It doesn’t have a mandate of being anything more than what it is, which is an odd thing, because this world is made up of people who are always trying to prove something.”

“I have always believed in the power of art to bring people together. I guess that’s why I have been doing this for 47 years, really, is to be a bit of a vessel for that. That’s always been my intention and my belief to inspire people to be a little more loving. Art has no mandate; you know what I mean? It doesn’t have a mandate of being anything more than what it is, which is an odd thing, because this world is made up of people who are always trying to prove something.”

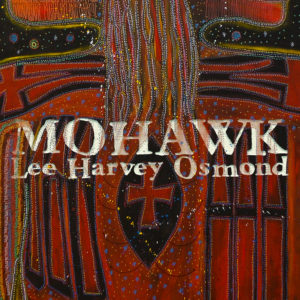

For decades, Wilson really hasn’t had anything to prove to the music industry or music fans with his prolific and profound output as a solo artist, through his gritty, badass rock band Junkhouse and through his continuing fruitful collaboration with Stephen Fearing and Colin Linden in Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, or his latest project, Lee Harvey Osmond, which features Wilson alongside members of the Skydiggers and Cowboy Junkies.

He is currently set to play a number of concerts and festivals, as well as speaking engagements throughout the late spring and early summer, including at Hugh’s Room in Toronto on May 16, and at the Wakefield Writer’s Festival in Wakefield Quebec on May 24. He is also appearing at the Burlington Sound of Music Festival on June 15, and at Centre in the Square in Kitchener on Oct. 17.

“Some of these shows haven’t really been like Lee Harvey Osmond band shows. It is more like a literary recital which I have been performing for about the last year, mostly with symphony orchestras like the National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa and a chamber orchestra that I work with regularly, the Hamilton Philharmonic. But what I am able to do with this show is strip it down to just piano and myself. So, I bring my piano played with me, and we perform songs that I have written, inspired by the book that I wrote, Beautiful Scars, along with a bunch of Junkhouse and Blackie & The Rodeo Kings and a lot of focus on Lee Harvey Osmond and our new album Mohawk,” Wilson said.

“What was happening was a lot of the writers festivals asked me to bring my guitar. Well, no, I don’t want to bring my guitar but you know what, since you want some music, I will bring my piano player and we will perform some songs and some readings from the show. So, that’s how this kind of evolved. Now the show is well established as far as what I do, and as far as what people call it, I don’t give a sh**.”

Mohawk was obviously shaped thematically, tonally and musically but the great revelation in Wilson’s life, which he recounted to Music Life Magazine in brief.

“I was quite a revelation I have to tell you. And it’s one that has inspired my visual art. I have a travelling art exhibit that is going to be going across Canada over the next two years that is called Beautiful Scars: Mohawk Warriors, Hunters and Chiefs. And I am also writing another book. When you’re in that circle of creativity when one discipline feeds off the other, the music definitely gets shaped by this story as well. And if it’s not shaped literally, then definitely the spirit of the music is there,” he explained.

“And it started a little over two and a half years ago. I was going on a speaking tour, and they gave me a handler and I got in the limousine and the handler said, ‘you know I am really excited. I am a big fan of yours. This is going to be great.’ And then she said, ‘you don’t know this, but your family, Bunny and George Wilson, and my family were friends.’ I told her that Bunny and George didn’t have any friends in Hamilton. They were really old; George was a tail gunner in a Lancaster bomber in the Second World War, the so-called ‘suicide seat.’ He got hit and had a massive head injury and was totally blind, so it was a rather dark, shut-down household.

“And it started a little over two and a half years ago. I was going on a speaking tour, and they gave me a handler and I got in the limousine and the handler said, ‘you know I am really excited. I am a big fan of yours. This is going to be great.’ And then she said, ‘you don’t know this, but your family, Bunny and George Wilson, and my family were friends.’ I told her that Bunny and George didn’t have any friends in Hamilton. They were really old; George was a tail gunner in a Lancaster bomber in the Second World War, the so-called ‘suicide seat.’ He got hit and had a massive head injury and was totally blind, so it was a rather dark, shut-down household.

“She said to me, ‘no, my grandmother was friends with Bunny. Her name was Mary Brennon.’ And I remember her grandmother’s name, and as a matter of fact, she said that they were so close that her grandmother was there the day I was adopted by Bunny and George. All I could say was, ‘what?’ I didn’t have any idea about any of that. So, that was kind of where this journey took off from.

“And it’s been an absolute trip. Not only has it been a physical journey, but I believe it’s the beginning of the journey that I am going to be on for the rest of my life, which is to explore my culture and where my culture comes from and where it’s going. And I am in no rush. It took me 50 odd years to get here, so I am really in no hurry to learn everything. The stuff will come. Things are definitely a little more spiritual now. Things are going to come to me in their own time. There are some things we can’t guide in this world and this is likely one of them.”

It is an interesting and enlightening journey for sure, and one that is all the more compelling because of Wilson’s commitment to sharing much of it through his music, his public speaking, his writing and his visual art.

For more information, including tour dates, visit https://tomwilsononline.com.

- Jim Barber is a veteran award-winning journalist and author based in Napanee, ON, who has been writing about music and musicians for a quarter of a century. Besides his journalistic endeavours, he now works as a communications and marketing specialist. Contact him at jimbarberwritingservices@gmail.com.

SHARE THIS POST: